Performance problems are rarely solved with clever tricks. Most of the time, they’re solved by understanding what you’re actually shipping to users. Next.js bundle size optimization is one of the most effective ways to improve an application’s performance in large React applications.

In this case, I was working on the DieatIdea‘s operations dashboard built with Next.js by a previous vendor. The application worked well functionally, but initial page loads felt heavier than they needed to be. My goal was clear and deliberately constrained:

reduce the amount of JavaScript users download and parse on first load — without breaking any existing functionality.

Below you can find how I analyzed the bundle, identified the real sources of bloat, and reduced the initial JavaScript payload by 40–75%, using safe, incremental techniques with AI assistance, obviously.

Why Bundle Size Still Matters (Even for Internal Tools)

Every kilobyte of JavaScript has a cost:

- Network transfer

- Parsing and execution time

- Memory usage

- Delayed interactivity

Even in internal tools, large bundles hurt:

- Slower initial loads

- Sluggish dashboards on less powerful machines

Rather than guessing where the problem was, I started by measuring.

Phase 1: Diagnosis Before Action

For Next.js applications, the most effective way to understand bundle composition is @next/bundle-analyzer. It generates an interactive treemap that shows exactly which files and dependencies end up in your final JavaScript bundles.

npm install @next/bundle-analyzer --save-dev

ANALYZE=true npm run build --prefix This setup keeps the analyzer out of normal development builds while giving full visibility in production mode.

What the Analyzer Revealed

The first report was immediately revealing.

Problem A: Heavy Third-Party Libraries in the Shared Bundle

Several large libraries were included in the main shared bundle, meaning they were downloaded on every page, even when unused:

xlsx(Excel export): ~896 KB@emoji-mart/data(emoji picker): ~415 KBchart.js(charts): ~403 KB

These features were useful — but not universally needed.

Phase 2: Strategy and Trade-offs

At this point, the strategy became clear: aggressively code-split the application.

Why Dynamic Imports

In a Next.js application, the most idiomatic and lowest-risk way to do this is through dynamic imports.

I used next/dynamic because it:

- Splits components and their dependencies into separate chunks

- Supports loading states

- Allows explicit control over server-side rendering

- Works with the framework not against it

Alternatives I Considered (and Rejected/KIV)

- Replacing libraries like

xlsxwith smaller alternatives

→ Risky, high regression potential, unnecessary for this goal - Manual Webpack configuration

→ Quite complex and largely redundant in Next.js

Dynamic imports offered the biggest performance gains with the lowest risk.

Phase 3: Execution — One Optimization at a Time

Lazy-Loading xlsx (On Demand)

Although xlsx was used in a utility function, it still bloated the shared bundle.

The fix was simple but effective:

- Convert the function to

async - Import the library only whenever needed

export async function exportToExcel(data) {

const xlxs = await import("xlsx");

// export logic here

}Now, the library is downloaded only when a user clicks “Export”.

Optimizing the Emoji Picker

The emoji picker required a two-step optimization:

- Dynamically import the picker component

- Lazily load the emoji dataset only when the picker is opened

useEffect(() => {

if (showEmojis) {

import("@emoji-mart/data").then(setEmojiData);

}

}, [showEmojis]);This ensured that 100 of kilobytes of emoji data were not part of the initial page load.

Splitting Chart.js Out of the Dashboard

Charts are visually important, but they don’t need to block the initial render.

const barChart = dynamic(

() => import("react-chartjs-2").then(m => m.Bar),

{ ssr: false }

);Breaking Up the Component Barrel File

This was the most labor-intensive change — and the most impactful.

Instead of importing from a barrel file:

import { DashboardMain } from "@/components";

I replaced these with direct, dynamic imports:

const DashboardMain = dynamic(

() => import("@/components/Dashboard"),

{

ssr: false,

loading: () => <LoadingSpinner />,

}

);Thinking why I disabled SSR?

For an internal operations dashboard, disabling SSR was an intentional trade-off:

- Smaller initial JavaScript payload

- No SEO requirements

- Less server load

A Detour: When Refactoring Reveals Hidden Problems

As the refactoring progressed, I used Jules AI as a coding assistant to speed up the repetitive changes. It helped restructure imports, suggest dynamic boundaries, and reduce manual effort.

For the most part, this worked well — until something felt off.

The application still built successfully, but a few components behaved inconsistently at runtime. There were no obvious errors, just subtle misbehavior. Bingo! After tracing the import graph, the issue became clear: a circular dependency had been introduced.

Noticed? The useEffect hook already had a dependency on emojiData which is updated inside the effect, creating an unnecessary dependency cycle.

Neither file was wrong in isolation, but together they formed a loop that broke module initialization order, dangerous situation in React and Next.js applications.

The fix required stepping back. The components weren’t meant to depend on each other; they were just sharing logic. Extracting that logic into a small, pure utility module immediately broke the cycle and clarified ownership.

This was a useful reminder:

AI can accelerate refactoring, but architectural boundaries still require human judgment.

Phase 4: Measuring the Impact

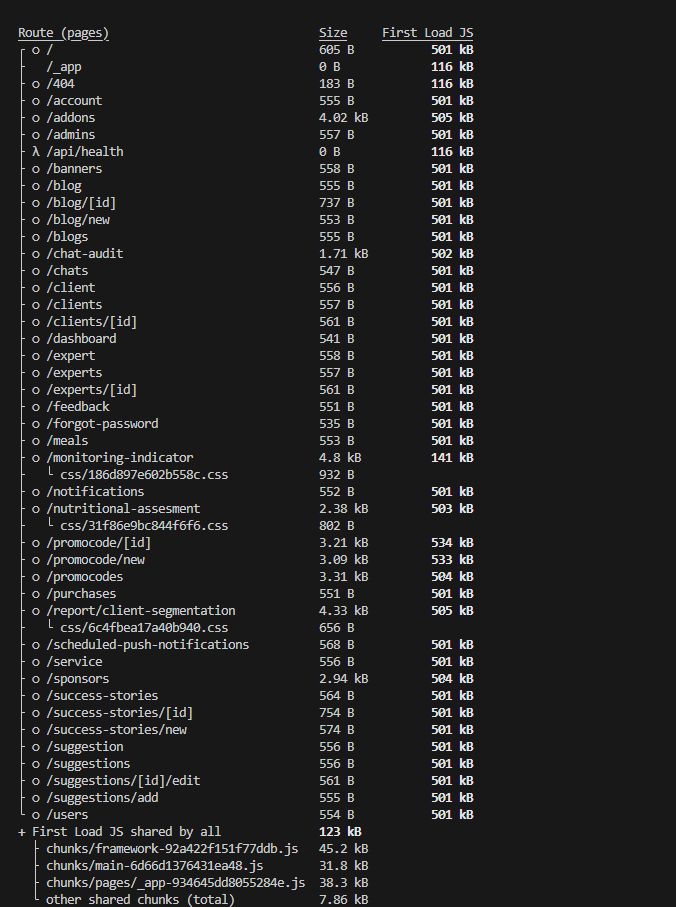

After all changes were complete, I re-ran the bundle analyzer.

Before:

- First Load JS: ~501 KB

After:

- First Load JS: 120–306 KB

- Shared bundle: ~125 KB

Most routes saw around 40% reduction in initial JavaScript payload, with a few routes seeing significantly larger gains once heavy, feature-specific dependencies were fully isolated.

[Image Placeholder: Before vs After bundle analyzer comparison]

Key Takeaways

- Always analyze before optimizing

- Dynamic imports are low-risk and high-impact

- Barrel files don’t scale well in large applications (how large is large that’s a good question, haha)

- Measure before and after every change

- AI tools accelerate work — but architectural judgment remains human!

- Have tests in place so you cna catch whats broken early.

Reducing bundle size isn’t about clever tricks. It’s about understanding what you ship, loading only what you need, and validating every trade-off.